13 June 2019

2 + 2 = ?

We have been discussing whole school literacy and oracy recently and thinking about how we can best encourage students to read for pleasure and to be confident talking about their different subjects in class. If you think back to your own time at school, you will have had classmates that sat in terror at the thought of being asked a question, or, worse, being asked to read aloud in class. You may even have been that person. I’ve written before on the importance of reading for pleasure and how the right book can offer a different way of looking at the world or, alternatively, provide a form of escapism from difficult circumstances. 5 years ago, I was asked to speak with students about the books that had the biggest impact upon me as a child. The request came from a school initiative to encourage students to read for pleasure and I spent a happy evening sorting through a box of books that I’d kept from a shared childhood bedroom to my current home. The first book that really fired my imagination was bought for me by my Grandmother from a branch of Woolworth’s in the early 1980s. It was a compilation of short horror and suspense stories, featuring an attack on an Atlantic passenger ship by vampire bats, an idyllic late evening walk in the woods disturbed by a zombie and a werewolf attack on a couple whose car had broken down on a desolate road. The stories are interlinked in my mind with the music from Tales of the Unexpected and the horror double bills on BBC2 that I was never allowed to stay up and watch; Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes at tea time on a Friday represented my parentally imposed watershed. There were other books about football and some adventure stories that I enjoyed, but nothing that would be regarded as classic literature. Regardless of that, I loved reading and would happily read to zone out the noise generated by a busy house full of family members and neighbours.

confident talking about their different subjects in class. If you think back to your own time at school, you will have had classmates that sat in terror at the thought of being asked a question, or, worse, being asked to read aloud in class. You may even have been that person. I’ve written before on the importance of reading for pleasure and how the right book can offer a different way of looking at the world or, alternatively, provide a form of escapism from difficult circumstances. 5 years ago, I was asked to speak with students about the books that had the biggest impact upon me as a child. The request came from a school initiative to encourage students to read for pleasure and I spent a happy evening sorting through a box of books that I’d kept from a shared childhood bedroom to my current home. The first book that really fired my imagination was bought for me by my Grandmother from a branch of Woolworth’s in the early 1980s. It was a compilation of short horror and suspense stories, featuring an attack on an Atlantic passenger ship by vampire bats, an idyllic late evening walk in the woods disturbed by a zombie and a werewolf attack on a couple whose car had broken down on a desolate road. The stories are interlinked in my mind with the music from Tales of the Unexpected and the horror double bills on BBC2 that I was never allowed to stay up and watch; Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes at tea time on a Friday represented my parentally imposed watershed. There were other books about football and some adventure stories that I enjoyed, but nothing that would be regarded as classic literature. Regardless of that, I loved reading and would happily read to zone out the noise generated by a busy house full of family members and neighbours.

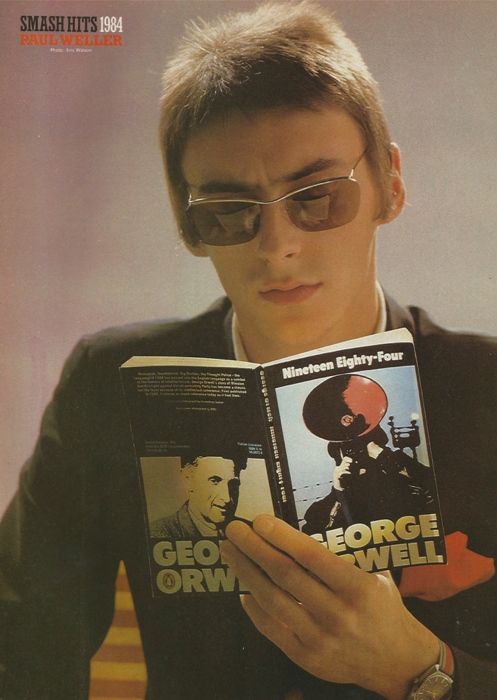

The first book that really affected me as a teenager was Nineteen Eighty Four, published 70 years ago and recently the subject of an excellent ‘biography’ by Dorian Lynskey, The Ministry of Truth. At the time I was a huge fan of Paul Weller and a photograph of him reading a copy in Smash Hits (in 1984, when I was 13) made me seek it out from the local Library. I’m currently re-reading the book and I was surprised by how much of it I remembered,  particularly the way in which I had visualised certain sections; Winston’s visit to Mr Charrington’s antique shop, his difficulty climbing the stairs, nursery rhymes and an elderly prole singing. It was also clear to me that, as a 13 year old, I had missed many of the more complex satirical points about language and the threat of totalitarianism; that nothing is real and everything is possible unless people remain vigilant. Dorian Lynskey’s book provides context regarding the genus of the book, it’s place within a gene of novels suggesting alternative futures, the difficulty that Orwell had completing it and the manner in which each new generation has viewed some aspect of the book as holding a mirror to contemporary society. For example, he references the 10,000 percent increase in sales after Donald Trump’s ‘not lies, but alternative facts’ inauguration of January 2017. My favourite parts of the book actually relate to Orwell’s penultimate novel, Animal Farm. It is

particularly the way in which I had visualised certain sections; Winston’s visit to Mr Charrington’s antique shop, his difficulty climbing the stairs, nursery rhymes and an elderly prole singing. It was also clear to me that, as a 13 year old, I had missed many of the more complex satirical points about language and the threat of totalitarianism; that nothing is real and everything is possible unless people remain vigilant. Dorian Lynskey’s book provides context regarding the genus of the book, it’s place within a gene of novels suggesting alternative futures, the difficulty that Orwell had completing it and the manner in which each new generation has viewed some aspect of the book as holding a mirror to contemporary society. For example, he references the 10,000 percent increase in sales after Donald Trump’s ‘not lies, but alternative facts’ inauguration of January 2017. My favourite parts of the book actually relate to Orwell’s penultimate novel, Animal Farm. It is  a widely reported fact that the CIA bought the rights to film the book via a shell company and were responsible for the famous cartoon version from 1954. They demanded changes to the script because they were financing the production, amongst many of their rejected suggestions was a poster campaign that would reference ‘Pig Brother’, that Napoleon and Snowball should have the same facial hair as Stalin and Trotsky and that there should be an alternative ending, in which Napoleon sends a porcine agent to Mexico by aeroplane to kill Snowball. If I hadn’t read Nineteen Eighty Four in 1984, I would not have read Animal Farm and a number of other books. Each new book takes you off in a different direction.

a widely reported fact that the CIA bought the rights to film the book via a shell company and were responsible for the famous cartoon version from 1954. They demanded changes to the script because they were financing the production, amongst many of their rejected suggestions was a poster campaign that would reference ‘Pig Brother’, that Napoleon and Snowball should have the same facial hair as Stalin and Trotsky and that there should be an alternative ending, in which Napoleon sends a porcine agent to Mexico by aeroplane to kill Snowball. If I hadn’t read Nineteen Eighty Four in 1984, I would not have read Animal Farm and a number of other books. Each new book takes you off in a different direction.

We intend to focus on literacy and oracy during the next school year and we want to encourage as many students, staff and parents as possible to read 20 books across the school year, regardless of genre. Recommending a book that someone goes on to enjoy is a great pleasure in its own right. With that in mind, I asked members of our school leadership team to share the books that had the biggest impact upon them when they were young. Below are the books that have stayed with them.

Mr Bowman:When I was at school we read The Pearl by John Steinbeck. It's a story of a poor pearl diver who finds a huge pearl that would make him extremely rich. He hides the pearl in his hut until he decides who to sell it to. During the night his baby son is bitten by a scorpion and becomes extremely ill, indeed close to death. Once the doctor finds out about the pearl he refuses to help until he is paid. I'll not spoil the end, I'll let you read it for yourself! This story meant a lot to me as at highlighted that greed and power of rich and influential people has a detrimental effect on the poor. It made me realise that supporting those less fortunate and not taking advantage of our position of relative wealth is important. In my opinion supporting others is the most important thing in life and one of the main reasons I came into teaching.

Mr Bowman:When I was at school we read The Pearl by John Steinbeck. It's a story of a poor pearl diver who finds a huge pearl that would make him extremely rich. He hides the pearl in his hut until he decides who to sell it to. During the night his baby son is bitten by a scorpion and becomes extremely ill, indeed close to death. Once the doctor finds out about the pearl he refuses to help until he is paid. I'll not spoil the end, I'll let you read it for yourself! This story meant a lot to me as at highlighted that greed and power of rich and influential people has a detrimental effect on the poor. It made me realise that supporting those less fortunate and not taking advantage of our position of relative wealth is important. In my opinion supporting others is the most important thing in life and one of the main reasons I came into teaching.

Miss Forbes:I was obsessed with Judy Blume books; it was like they narrated my childhood and answered the questions I didn’t want to ask my parents. They made me laugh and cry! They made me understand that it was difficult to be a teenager, but that everyone was on their own journey and navigating it in their own way (and none of us really knew what we were doing). I think what I got from these books was that it was OK just to be me. Blubber deals with bullying, friendships and making a stand. It also looks at how adults deal with certain situations and the importance of their input. Sadly, it shows that children don’t always speak out and that things don’t always turn out the way we would like them to.

Miss Forbes:I was obsessed with Judy Blume books; it was like they narrated my childhood and answered the questions I didn’t want to ask my parents. They made me laugh and cry! They made me understand that it was difficult to be a teenager, but that everyone was on their own journey and navigating it in their own way (and none of us really knew what we were doing). I think what I got from these books was that it was OK just to be me. Blubber deals with bullying, friendships and making a stand. It also looks at how adults deal with certain situations and the importance of their input. Sadly, it shows that children don’t always speak out and that things don’t always turn out the way we would like them to.

.jpg) Mrs Lennon:Tai-Pan (James Clavell)by, which is set around the Opium Wars and the foundation of Hong Kong as a trading centre, this book sparked my interest in business / commerce. The key themes of business, power and politics are interwoven with the often complex family story of the protagonist – Dirk Struan. The differences between British and Chinese culture are explored and the thing that really struck me was the planning timeframe – in the book, the Chinese culture supported planning very much over a longer term rather than the short term gains pursued by many of the British characters involved. Dirk Struan became ‘Tai-Pan’ – Supreme leader – largely because he was able to take the best bits from both cultures rather than stick to the traditional way of either culture. I think about these themes often – especially when teaching the ‘Global Business’ theme at A level. The depiction of Dirk’s back story, starting as a powder monkey (aged 7) in 1805 really brings the character, and the time period, to life. Also, this was the first book that made me realise that heroes can do things I might disagree with (often strongly) but still be very charismatic.

Mrs Lennon:Tai-Pan (James Clavell)by, which is set around the Opium Wars and the foundation of Hong Kong as a trading centre, this book sparked my interest in business / commerce. The key themes of business, power and politics are interwoven with the often complex family story of the protagonist – Dirk Struan. The differences between British and Chinese culture are explored and the thing that really struck me was the planning timeframe – in the book, the Chinese culture supported planning very much over a longer term rather than the short term gains pursued by many of the British characters involved. Dirk Struan became ‘Tai-Pan’ – Supreme leader – largely because he was able to take the best bits from both cultures rather than stick to the traditional way of either culture. I think about these themes often – especially when teaching the ‘Global Business’ theme at A level. The depiction of Dirk’s back story, starting as a powder monkey (aged 7) in 1805 really brings the character, and the time period, to life. Also, this was the first book that made me realise that heroes can do things I might disagree with (often strongly) but still be very charismatic.

Mr McArdle:I read a lot of non-fiction although I also read Lord of the Rings (twice) and I think Tarka the Otter helped to inspire an early fascination with nature. Fitzroy Mclean's Eastern Approaches made me want to travel but much of my reading was about mountaineering and polar exploration. Rock climbing and later mountaineering allowed me find out a lot about myself. One book which stands out is Heinrich Harrer's Seven Years in Tibet, now a well-known film. I didn't have much experience of German or Austrian heroes and no idea of the culture of countries as exotic as Tibet. The traumatic experiences of the people of Tibet since the Chinese invasion rarely make the news. It taught me to look beyond the headlines and not to assume that the adults in my life knew everything.

Mr McArdle:I read a lot of non-fiction although I also read Lord of the Rings (twice) and I think Tarka the Otter helped to inspire an early fascination with nature. Fitzroy Mclean's Eastern Approaches made me want to travel but much of my reading was about mountaineering and polar exploration. Rock climbing and later mountaineering allowed me find out a lot about myself. One book which stands out is Heinrich Harrer's Seven Years in Tibet, now a well-known film. I didn't have much experience of German or Austrian heroes and no idea of the culture of countries as exotic as Tibet. The traumatic experiences of the people of Tibet since the Chinese invasion rarely make the news. It taught me to look beyond the headlines and not to assume that the adults in my life knew everything.

Mrs Suleman:I've never been into fiction and prefer reading for facts. Having said that, I liked Paulo Coehlo's books; good short stories you can get into. The Alchemist was a good book about following your dreams and sometimes not realising you have found what you're looking for, true wealth is not measured by material possessions.

Mrs Suleman:I've never been into fiction and prefer reading for facts. Having said that, I liked Paulo Coehlo's books; good short stories you can get into. The Alchemist was a good book about following your dreams and sometimes not realising you have found what you're looking for, true wealth is not measured by material possessions.

Mr Wilbraham:As a Year 6 student Robert Westall’s The Machine Gunners. Reading this book at primary school was such an exciting experience. Westall manages to merge the impact of WW2 on Blitz Britain with a story that is essentially about teenagers’ relationships and everyday lives. Reading Westall brought history to life in a way that had previously, never seemed so exiting or relevant to my own life or learning. I was hooked!In Year 9 Bill Bryson’s Neither Here Nor There excited due to its communication of the joys and perils of travel across Europe, not least his experiences with his friend Stephen Katz. Every page was full of information that encouraged you to get out there and travel yourself, but most importantly, he was so funny. Bryson remains one of my favourite authors for his humour, fundamental decency and his genuine enthusiasm for learning.

Mr Wilbraham:As a Year 6 student Robert Westall’s The Machine Gunners. Reading this book at primary school was such an exciting experience. Westall manages to merge the impact of WW2 on Blitz Britain with a story that is essentially about teenagers’ relationships and everyday lives. Reading Westall brought history to life in a way that had previously, never seemed so exiting or relevant to my own life or learning. I was hooked!In Year 9 Bill Bryson’s Neither Here Nor There excited due to its communication of the joys and perils of travel across Europe, not least his experiences with his friend Stephen Katz. Every page was full of information that encouraged you to get out there and travel yourself, but most importantly, he was so funny. Bryson remains one of my favourite authors for his humour, fundamental decency and his genuine enthusiasm for learning.

Mr Wright:Could I be slightly clichéd and go for the Catcher in the Rye. I was 14, I thought it was meant to be cool and found it was really cool. For years I would give other copies to other people, re-read it and feel that I might be embracing some of what Holden Caulfield stood for. Today I remember it fondly but in what I imagine Holden would find as a patronising manner. I think it's the sort of book it's important to read, identify with and then grow out of. I'd be suspicious of any teenager who couldn't identify with it at all and suspicious of any adult who did so.

Mr Wright:Could I be slightly clichéd and go for the Catcher in the Rye. I was 14, I thought it was meant to be cool and found it was really cool. For years I would give other copies to other people, re-read it and feel that I might be embracing some of what Holden Caulfield stood for. Today I remember it fondly but in what I imagine Holden would find as a patronising manner. I think it's the sort of book it's important to read, identify with and then grow out of. I'd be suspicious of any teenager who couldn't identify with it at all and suspicious of any adult who did so.

Which 20 books will you read across the year? We will offer an update each half-term of what our teachers and students are reading and hopefully something will inspire you.

Mr O’Sullivan