4 May 2018

‘Fake news’ is a current obsession. Fabrication and false narratives undermine public discourse and confidence in institutions. David Clark, an advisor to Tony Blair’s 1997 government noted recently that some governments are currently trying to lead the world into a ‘wilderness of mirrors.’ My response to this would quite simply be, ‘Where’s Trotsky?’ (Above). The most disturbing aspect of this is not that individuals or governments might falsify or manipulate the truth – that has been a reoccurring theme of history – but the increasingly sophisticated manner in which it can be done.

The usual way to address this is to encourage students to go the origin or source of the information that they are accessing. To encourage scepticism, fact checking and the development of the ‘media literacy’ necessary to identify disinformation. This has been sound advice for decades. The two images above seem quaint now, but generated significant controversy when they were first published. Elsie Wright’s sequence of ‘Cottingley Fairies’ photographs were met with general bemusement in 1917 as it was common knowledge that fairies (Spoiler alert for younger readers) didn’t exist. This didn’t stop Sir Arthur Conan Doyle describing them as evidence of ‘a significant psychic phenomena.’ He also believed that Ada Deane’s ‘photograph’ of the souls of the British war dead rising above a London crowd on Armistice Day (11th November) had captured a ‘true spiritualist moment.’ Some people will believe anything, but most people have the necessary critical facilities to distinguish between fact, fabrication and interpretation.

The usual way to address this is to encourage students to go the origin or source of the information that they are accessing. To encourage scepticism, fact checking and the development of the ‘media literacy’ necessary to identify disinformation. This has been sound advice for decades. The two images above seem quaint now, but generated significant controversy when they were first published. Elsie Wright’s sequence of ‘Cottingley Fairies’ photographs were met with general bemusement in 1917 as it was common knowledge that fairies (Spoiler alert for younger readers) didn’t exist. This didn’t stop Sir Arthur Conan Doyle describing them as evidence of ‘a significant psychic phenomena.’ He also believed that Ada Deane’s ‘photograph’ of the souls of the British war dead rising above a London crowd on Armistice Day (11th November) had captured a ‘true spiritualist moment.’ Some people will believe anything, but most people have the necessary critical facilities to distinguish between fact, fabrication and interpretation.

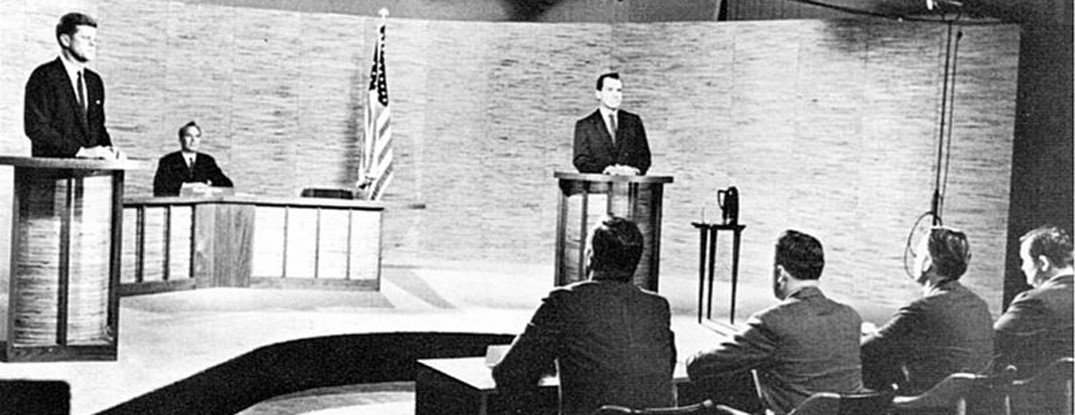

In my first three years at Durham Johnston I taught A level politics. The American part of the course looked at the relative importance of presidential debates within the US political system. When I was training to be a teacher I was told by my grizzled, been there, seen it, done it mentor that the best measure of any prospective history teacher was, ‘whether or not they could tell a good story.’ The 1960 Presidential debate, between John F Kennedy and Richard Nixon, offers such a tale and I would share it with my politics classes. Before the debate Nixon was convinced that he would win; he had been Vice-President and had much greater experience. In the run up to the debate, however, he had injured his knee; on his way into the TV studio he bashed his sensitive leg painfully against a door. In the studio the TV producer suggested that make up would cover his 5 o’clock shadow and make him appear more telegenic. He accepted the advice. In the actual debate viewers commented upon the gulf between the two candidates. Nixon, stooped over with his sore knee began to sweat under the studio lights, causing his make up to melt. He seemed shifty and untrustworthy. Kennedy, by comparison, appeared presidential. Television viewers believed JFK to be the clear winner, the majority of radio listeners however, thought that Nixon had won. It suggests, quite clearly, that what we see is different to what we hear, or read.

However, 1960 is not 2018. When Kennedy was assassinated in 1963 he had been planning to deliver a speech on education; historians often call it his ‘lost speech.’ It is lost no longer. In, what has been referred to as, ‘ an extraordinary piece of technical virtuosity,’ sound engineers have used 116,777 sound units from 831 of his speeches and radio addresses to create an approximation of JFK reading the text. It sounds a little clunky, but it is Kennedy delivering his speech. It is quite an advance from Trotsky being physically cut out of photographs in the 1930s, but at least they are his words.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/uk-scotland-43436361/john-f-kennedy-s-lost-last-speech-recreated

There are examples of far more sophisticated, yet worrying, techniques that are now possible. Researchers at the University of Washington have managed to turn audio clips into realistic videos of people speaking. They chose Barack Obama to demonstrate this technological advance and created footage of him discussing fatherhood and terrorism; all generated from existing weekly videos posted by the White House on completely different subjects. They used a neural network to model the shape of Obama’s mouth and then, literally, put different words into it. Without context, it is real.

How can we distinguish between reality and rhetoric when such things are possible? The answer is that we probably won’t be able to. This is the world that our young people are growing up in and whilst they can use the technology, they don’t necessarily have the ethical framework in which to effectively critique it.

These things are on my mind because we have been discussing ‘What kind of people we are?’ in meetings this week. The Association of School and College Leaders have focused since last June on Ethical Leadership. They have asked fundamental questions, such as ‘What are Schools for?’ identifying 7 virtues for school leaders, based upon the Nolan Principles of Public Life. The seventh virtue is honesty; the need to be truthful. We are currently thinking about the best way to share these ideas with our young people, but it is worth considering the place of personal honesty in the wider societal context of deceit, fabrication and untruth. How can young people navigate a world in which technology allows us to hear a presidential speech from beyond the grave in one instance and the 44th President can appear to advance arguments that he has never made in another? Our duty is to model honesty and integrity and to develop that same virtues for our students.

Make yourself an honest man, and then you may be sure there is one less rascal in the world. Thomas Carlyle

Mr O’Sullivan